These days, Mr. Breashears is still climbing the Himalayas, but he is lugging more than pitons and ice axes. He’s also carrying special cameras to document stunning declines in glaciers on the roof of the world.

Mr. Breashears first reached the top of Everest in 1983, and in many subsequent trips to the region he noticed the topography changing, the glaciers shrinking. So he dug out archive photos from early Himalayan expeditions, and then journeyed across ridges and crevasses to photograph from the exact same spots.

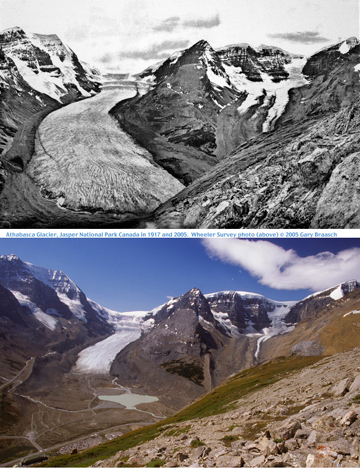

The pairs of matched photographs, old and new, are staggering. Time and again, the same glaciers have shrunk drastically in every direction, often losing hundreds of feet in height.

“I was just incredulous,” he told me. “We took measurements with laser rangefinders to measure the loss of height of the glaciers. The drop was often the equivalent of a 35- or 40-story building.”

Mr. Breashears led me through a display of these paired photographs at the Asia Society in New York. One 1921 photo by George Mallory, the famous mountaineer who died near the summit of Everest three years later, shows the Main Rongbuk Glacier. Mr. Breashears located the very spot from which Mallory had snapped that photo and took another — only it is a different scene, because the glacier has lost 330 feet of vertical ice.

Some research in social psychology suggests that our brains are not well adapted to protect ourselves from gradually encroaching harms. We evolved to be wary of saber-toothed tigers and blizzards, but not of climate change — and maybe that’s also why we in the news media tend to cover weather but not climate. The upshot is that we’re horrifyingly nonchalant at the prospect that rising carbon emissions may devastate our favorite planet.

NASA says that the January-through-June period this year was the hottest globally since measurements began in 1880. The Web site ClimateProgress.org, which calls for more action on climate change, suggests that 2010 is likely to be the warmest year on record. Likewise, the Global Snow Lab at Rutgers University says that the months of May and June had the lowest snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere since the lab began satellite observations in 1967.

So signs of danger abound, but like the proverbial slow-boiling frog, we seem unable to rouse ourselves.

(Actually, it seems that frogs will not remain in a beaker that is slowly heated. Snopes.com quotes a distinguished zoologist as saying that frogs become agitated as the temperature slowly rises and struggle to escape, although it does not specify how the zoologist knows this.)

From our own beaker, we’ve watched with glazed eyes as glaciers have retreated worldwide. Glacier National Park now has only about 25 glaciers, compared with around 150 a century ago. In the Himalayas, the shrinkage seems to be accelerating, with Chinese scientific measurements suggesting that some glaciers are now losing up to 26 feet in height per year.

Orville Schell, who runs China programs at the Asia Society, described passing a series of pagodas as he approached the Mingyong Glacier on the Tibetan plateau. The pagodas were viewing platforms, and had to be rebuilt as the glacier retreated: this monumental, almost eternal force of nature seemed mortally wounded.

“A glacier is a giant part of the alpine landscape, something we always saw as immortal,” Mr. Schell said. “But now this glacier is dying before our eyes.”

An Indian glaciologist, Syed Iqbal Hasnain, now at the Stimson Center in Washington, told me that most Himalayan glaciers are in retreat for three reasons. First is the overall warming tied to carbon emissions. Second, rain and snow patterns are changing, so that less new snow is added to replace what melts. Third, pollution from trucks and smoke covers glaciers with carbon soot so that their surfaces become darker and less reflective — causing them to melt more quickly.

The retreat of the glaciers threatens agriculture downstream. A study published last month in Science magazine indicated that glacier melt is essential for the Indus and Brahmaputra rivers, while less important a component of the Ganges, Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The potential disappearance of the glaciers, the report said, is “threatening the food security of an estimated 60 million people” in the Indus and Brahmaputra basins.

We Americans have been galvanized by the oil spill on our gulf coast, because we see tar balls and dead sea birds as visceral reminders of our hubris in deep sea drilling. The melting glaciers should be a similar warning of our hubris — and of the consequences that the earth will face for centuries unless we address carbon emissions today.

No comments:

Post a Comment